Picture your strategy as a journey guiding your organization from its current position to a new state. This future destination should be articulated through a Vision statement—a vibrant, inspiring yet attainable portrayal of how the company will appear if its strategy proves successful. Since words might be subject to interpretation, however, it is important to also articulate the Level of Ambition—a set of measurable targets that will translate the Vision statement into numbers that can be tracked. Continuing with the journey metaphor, think of the Vision as a picture of the place you’re trying to reach and the Level of Ambition as its GPS coordinates. How do you go from your current state to that envisioned future? Charting the path to reach your ambition requires the definition of Strategic Priorities.

At its core, a Strategic Priority represents one of the fundamental decisions facing a leadership team. It is a choice because, while there may be various paths a company could pursue to achieve its Level of Ambition, resources are finite. Therefore, it becomes crucial to determine what actions to prioritize and what to forego, thus defining what truly matters.

The term “strategic” underscores the focus of this choice on either capitalizing on opportunities or mitigating threats—or sometimes, both. A robust strategic priority is one that not only seizes opportunities but also addresses potential threats. Conversely, if it targets something neither opportunistic nor threatening, it risks investing in irrelevant pursuits.

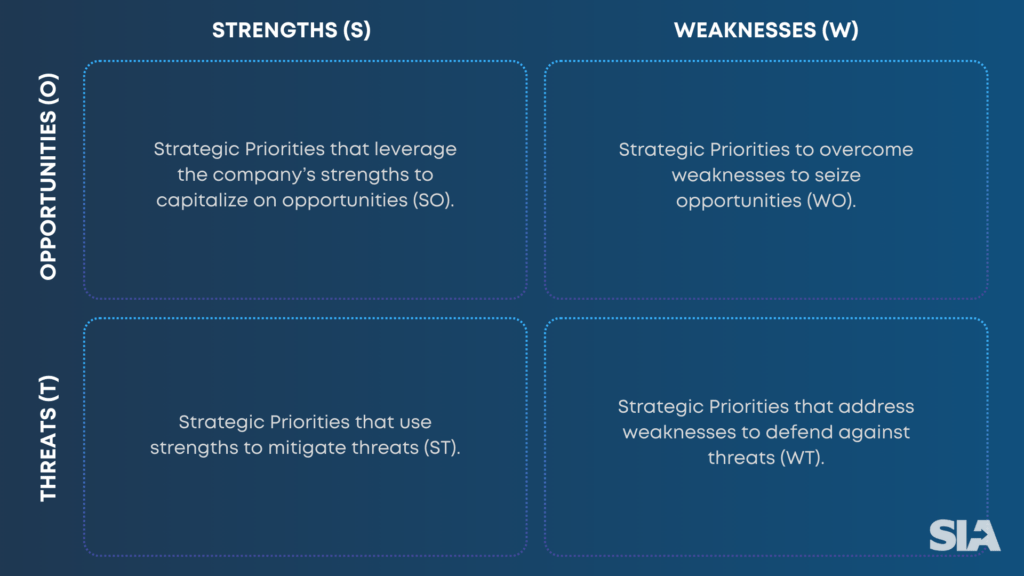

Strategic Priorities must be market-driven, stemming from a comprehensive analysis of the marketplace. Since they should align external inputs—Opportunities and Threats—with internal inputs—Strengths and Weaknesses, in order to identify Strategic Priorities the company should undertake two types of analysis: internal analysis, to identify its core strengths and weaknesses, and external analysis, to uncover available opportunities and potential threats. The most used tool to synthetize the internal and external analyses and a starting point for defining Strategic Priorities is the SWOT (Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, and Threats) analysis.

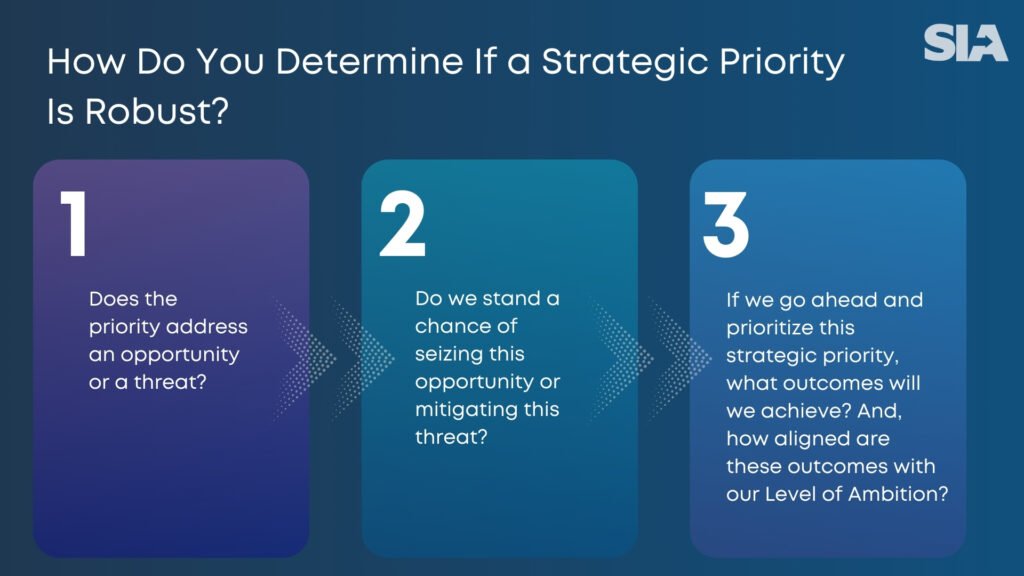

After conducting comprehensive internal and external analyses and generating a SWOT analysis, leaders might feel well-equipped to define robust Strategic Priorities. However, how can they be certain that the Strategic Priorities they have identified are indeed genuinely robust? They can undertake the following three checks.

First, they need to ask themselves: Does the priority address an opportunity or a threat? Too often, amidst the strategic journey planning, this crucial connection is overlooked. If the priority fails to address an opportunity or a threat, it is not strategic.

Second, and crucially, they need to ask themselves: Do we stand a chance of seizing this opportunity or mitigating this threat? To answer this question effectively, they must understand what is required to capitalize on the opportunity or tackle the threat—asking themselves, “What do I need to win?”—along with their proficiency in fulfilling those requirements—by considering, “Of these things that I need, are they strengths or weaknesses vis-à-vis the competition?”. Consequently, a strategic priority must not only address one or more opportunities and/or threats but, above all, leverage those areas within the operating model where strengths outweigh weaknesses.

Leaders often fall into the trap of choosing priorities based solely on the magnitude of opportunities and threats. Similarly, they frequently overreact by addressing weaknesses in descending order of magnitude, targeting the most significant weakness first. To avoid these traps and conduct these initial two checks appropriately, a very useful approach is the TOWS (Threats, Opportunities, Weaknesses, and Strengths) matrix. This tool extends the SWOT analysis by matching external opportunities and threats with internal strengths and weaknesses, thereby translating the identified insights into strategic actions.

For instance, let’s consider an opportunity that requires 10 factors to secure success. Among these, 7 are strengths, indicating that the company demonstrates superior performance relative to competitors, while 3 are weaknesses, meaning the company exhibits inferior performance or lacks them. This is an example of a strong strategic priority. Why? Because with 7 strengths, the company is likely to outperform competitors, who excel only in 3 areas where the company needs to improve.

Consider the reverse scenario: the company ventures into a domain where it has 8 weaknesses and only 2 strengths. The likelihood of encountering obstacles is much higher. This is the reason why, most of the time, great companies and their leaders opt not to pursue the biggest opportunity or tackle the greatest threat, but instead, choose to focus on those opportunities or threats where they stand a better chance of success.

This doesn’t mean they won’t pursue the larger opportunity, but it becomes a secondary priority. For instance, if there’s a larger opportunity where a company has many weaknesses, it might decide to start working on it to learn, recognizing that if it doesn’t take action, it will never improve. However, it’s not its primary focus because it doesn’t directly contribute to its objectives. This represents the second type of assessment that helps companies in ranking and prioritizing their strategic priorities.

Third, as a final acid test, leaders need to ask themselves: If we go ahead and prioritize this strategic priority, what outcomes will we achieve? And how aligned are these outcomes with our Level of Ambition? It could be the case that a company identifies a great opportunity and possesses the right strengths to address it, but if it’s not aligned with the ambition it has set, pursuing it may not be beneficial. Why?

Strategic Priorities are not tactical actions; they require prolonged effort over time, and typically, the results are not immediate. Adopting the Three Horizons of growth framework, [i] these priorities might yield results in the next 12-18 months if they fall within Horizon 1, and within 2 or 3 years if they fall within Horizon 2. However, if they fall within Horizon 3, results may take much longer to materialize, possibly never emerging or only doing so in the long term.

Therefore, the ultimate test for a strategic priority is: Does it bring me closer, and by how much, to my Vision and Level of Ambition? If it fails this criterion, despite passing the first two checks, it becomes a futile endeavor.

After defining sound and robust Strategic Priorities, the leadership team should allocate time to crafting Enabling Priorities. Unlike Strategic Priorities, which are focused on specific market spaces, Enabling Priorities address the internal workings of the organization. They are crucial for enhancing various functions and core business activities, aiming to answer the question: How will we strengthen the organization to enable it to achieve our Strategic Priorities? By addressing three key levers—Enabling Systems, People, and Organization—organizations assess whether they have the right digital infrastructure, skilled workforce, and organizational systems and processes to support their strategic objectives.

Furthermore, it’s crucial to bear in mind that both Strategic and Enabling priorities should be articulated using both words and numbers. As mentioned earlier when discussing the Level of Ambition, relying solely on words can lead to ambiguity, hence it’s vital to link each priority with a set of measurable impact indicators. These indicators quantify the effects of the Strategic Priorities on various metrics such as revenues, gross margin, operating expenses, as well as other non-financial metrics including market share, vitality index, Net Promoter Score, ESG rating, and many others. By aligning these impact measures with the Level of Ambition, companies can ensure that each priority contributes effectively to their ultimate vision.

After completing this step, the company is ready to embark on its journey, ensuring it avoids the three key reasons behind strategy execution failures.

[i] Mehrdad Baghai, Stephen Coley, and David White, The Alchemy of Growth: Practical Insights for Building the Enduring Enterprise (Reading, Massachusetts: Perseus Books, 1999).

Davide Sola and Jérôme Couturier, How to Think Strategically: Your Roadmap to Innovation and Results (Harlow, England; New York: Pearson, 2014).

Alan G. Lafley and Roger L. Martin, Playing to Win: How Strategy Really Works (Boston, Massachusetts: Harvard Business Review Press, 2013).

Richard W. Puyt, Finn Birger Lie, and Celeste P.M. Wilderom, “The origins of SWOT analysis,” Long Range Planning, Volume 56, Issue 3, 2023, 102304, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0024630123000110, accessed February 2024.

Heinz Weihrich, “The TOWS matrix—A tool for situational analysis,” Long Range Planning, Volume 15, Issue 2, 1982, Pages 54-66, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/0024630182901200, accessed February 2024.