In the course of my consulting work, I have often been asked whether developing a strategy at the group level is beneficial when managing a highly diversified group. I would like to take some time to explore a few aspects associated with this matter.

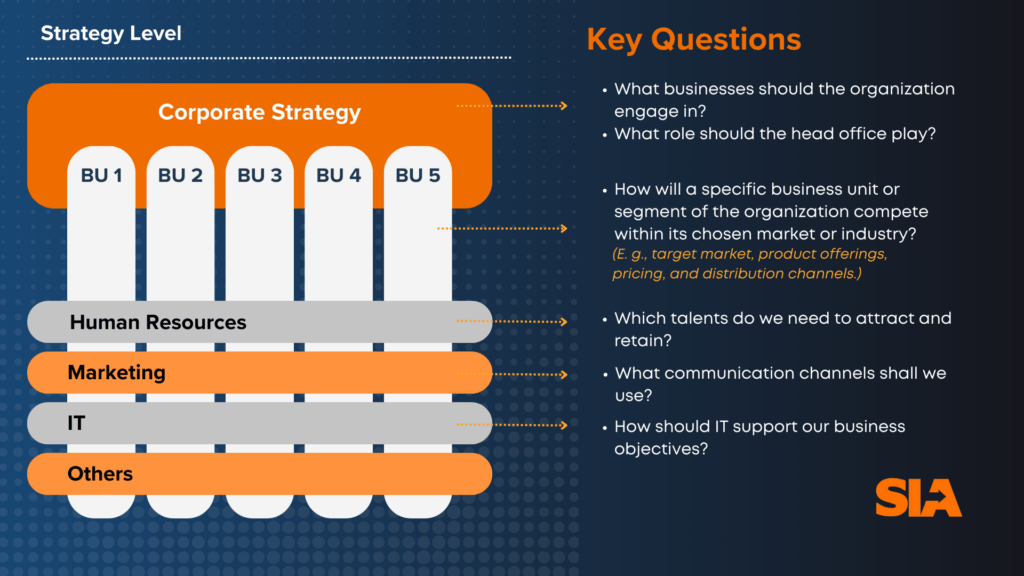

When discussing strategy, it is crucial to recognize the existence of at least three distinct levels: corporate, business, and functional strategy. At the corporate level, strategy revolves around addressing two fundamental questions: what businesses should the organization engage in? And, what role should the head office play?

Business strategy, on the other hand, focuses on answering the question: how will a specific business unit or segment of the organization compete within its chosen market or industry? This involves considerations such as target market, product offerings, pricing, and distribution channels, aiming to establish a sustainable edge over rivals.

Meanwhile, functional strategy tackles the question: how does each functional area (e.g., marketing, finance, operations) contribute to the achievement of overall business and corporate strategies? This entails aligning the activities of each functional area with broader business objectives and corporate goals. Let’s delve deeper into the first one—corporate strategy—and dispel some misconceptions surrounding it.

First, while the term “corporate” may suggest a focus on larger and complex-structured corporate entities, corporate strategy addresses a fundamental question regarding the overall direction and scope of the organization. As previously mentioned, it seeks to answer: In which businesses should the organization be involved?

This involves crucial decisions such as where to enter, where to exit, where to invest, and consequently, how to allocate resources across various business units or functions. Any organization, regardless of its size or structure, must address these essential questions. In other words, every company needs to formulate a comprehensive corporate or “company-wide” strategy.

The second key question of corporate strategy—What role does the head office play?—focuses on how the head office interacts with its business units. The underlying concept is that the head office should exert influence over its businesses in a manner that enables them to “create more value than any of their rivals would if they owned the same businesses”[i] —a concept referred to in strategy literature as “parenting advantage.” Therefore, to add value, the head office must identify opportunities for improvement within the businesses and determine how to intervene effectively to turn that improvement potential into reality.

The parenting potential takes on different connotations depending on the organization’s structure. In simplified terms, we can categorize companies into two types. The first type envisions a company as the aggregation of semi-independent organizations, each with distinct offerings, customer bases, and specific resources (e.g., assets, skills). This structure leads to a relatively lean head office.

On the other hand, the second type, offers products or services within the same or similar categories. The business units share common markets with significant overlap in their customer base, and the specificity of resources within each unit is relatively low. In this scenario, there is notably high integration among corporate functions, reflected in the considerable size of the corporate office.

In my experience, for the first type of highly diversified companies, parenting advantage primarily arises from knowledge sharing. This implies that the head office often has access to a wealth of resources, expertise, and best practices that it can effectively disseminate across various subsidiaries. Such knowledge sharing proves invaluable, as it serves to enhance the capabilities of individual units, thereby bolstering their competitiveness. Even though each business might be very different from the others—for instance, one dealing with farming products, another with construction products, another with financial services—this collaborative exchange of knowledge empowers individual units to formulate more effective business strategies, ultimately elevating their competitive edge.

For example, Jack Welch, during his 20-year tenure as CEO of the American multinational General Electric, placed significant importance on the sharing of best practices among the conglomerate’s divisions.[ii] Not only did he consider transferring “best practices across all the businesses, with lightning speed” as one of his key responsibilities as a business leader,[iii] but he also regarded best practices as one of the three key pillars of strategy formulation and execution.

In fact, he believed that strategy is unleashed when an organization has a learning culture in place, wherein people draw on best practices from both inside and outside the company, adapt them, and continuously improve them to pursue the chosen ways to gain sustainable competitive advantage. “Without this learning culture in place,” he stated, “any sustainable competitive advantage will not last.”[iv]

The second type of company, on the other hand, offers intriguing opportunities for parenting advantage. Take, for instance, a scenario in which all the diverse business units have a common need for the same raw material. Instead of each unit procuring the raw material independently, the head office can oversee the procurement process and collectively purchase the raw material for all its business units. This strategic approach leverages the combined volume, leading to more favorable pricing arrangements.

Another domain where parenting advantage proves powerful is in Research and Development (R&D). When business units lack the individual capacity in terms of skills and time to pursue extensive R&D initiatives, yet their operations share enough similarities for innovation to yield benefits for all of them, centralizing this function can generate a critical mass, ensuring the overall success of the company.

Take, for example, the Italian multinational company Ferrero. Its renowned Soremartec division is primarily responsible for the development and refinement of food products. This encompasses the creation of new food products and the improvement of existing ones, research into new raw materials, and the enhancement of raw materials’ organoleptic characteristics, shelf life, safety, and production costs. The division is also dedicated to discovering new packaging solutions or enhancing existing packaging to achieve optimal performance in terms of efficiency, shelf life, safety, environmental sustainability, and costs. Soremartec’s mission is to create and experiment with new products featuring a strong technological barrier, innovating significantly in existing industrial products to maintain and enhance a competitive advantage over rivals.[v] With product quality positioned at the core of its value proposition, Ferrero has made centralizing R&D a formidable source of parenting advantage.

Operations and brand management are other areas where parenting advantage may be applied. Through the standardization of processes, systems, or technologies across subsidiaries, a parent company can attain operational efficiencies and cost reduction. Consider, for instance, a centrally chosen and acquired SAP system implemented by the head office for all its business units. Additionally, the head office can invest in building a robust brand to positively influence the perception of its subsidiaries. The reputation of the parent company thus serves as a trust-building factor for customers and stakeholders across its diverse businesses.

Returning to the question of whether a highly diversified group can have a corporate strategy, the answer is affirmative. However, it is crucial to consider the two subquestions that corporate strategy must address. First, corporate strategy should involve decisions regarding the allocation of capital and resources, along with the definition of long-term objectives—the first subquestion. Additionally, for a diversified company, addressing the second subquestion is vital. It entails a careful examination to identify areas with parenting advantage, ensuring the head office creates rather than destroys value.

Davide Sola and Jérôme Couturier, How to Think Strategically: Your Roadmap to Innovation and Results (Harlow, England; New York: Pearson, 2014).

Michael E. Porter, “From Competitive Advantage to Corporate Strategy,” Harvard Business Review, May 1987, https://hbr.org/1987/05/from-competitive-advantage-to-corporate-strategy, accessed January 2024.

[i] Andrew Campbell, Michael Goold, and Marcus Alexander, “Corporate Strategy: The Quest for Parenting Advantage,” Harvard Business Review, March-April 1995, https://hbr.org/1995/03/corporate-strategy-the-quest-for-parenting-advantage, accessed January 2024.

[ii] Claudio Fernández-Aráoz, “Jack Welch’s Approach to Leadership,” Harvard Business Review, March 3, 2020, https://hbr.org/2020/03/jack-welchs-approach-to-leadership, accessed February 2024.

Harris Collingwood and Diane L. Coutu, “Jack on Jack: The HBR Interview,” Harvard Business Review, February 2002, https://hbr.org/2002/02/jack-on-jack-the-hbr-interview, accessed February 2024.

Bartlett, Christopher A., and Meg Wozny. “GE’s Two-Decade Transformation: Jack Welch’s Leadership.” Harvard Business School Case 399-150, April 1999. (Revised May 2005.)

[iii] Noel Tichy and Ram Charan, “Speed, Simplicity, Self-Confidence: An Interview with Jack Welch,” Harvard Business Review, September-October 1989, https://hbr.org/1989/09/speed-simplicity-self-confidence-an-interview-with-jack-welch, accessed February 2024.

[iv] Jack Welch and Suzy Welch, Winning (New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 2005.).

[v] Salvatore Giannella, Michele Ferrero: Condividere valori per creare valore (Milano: Salani Editore, 2023); Polo AGRIFOOD, “Socio Fondatori, Soremartec Italia S.R.L.,” https://www.poloagrifood.it/site/scheda.php?id_noticia=68, accessed January 2023.